Richard Sander’s lawsuit against the UC is more about politics than transparency

By Arthur Wang

Nov. 28, 2018 10:26 a.m.

Affirmative action’s days may be numbered due to an academic’s (pur)suit for the numbers.

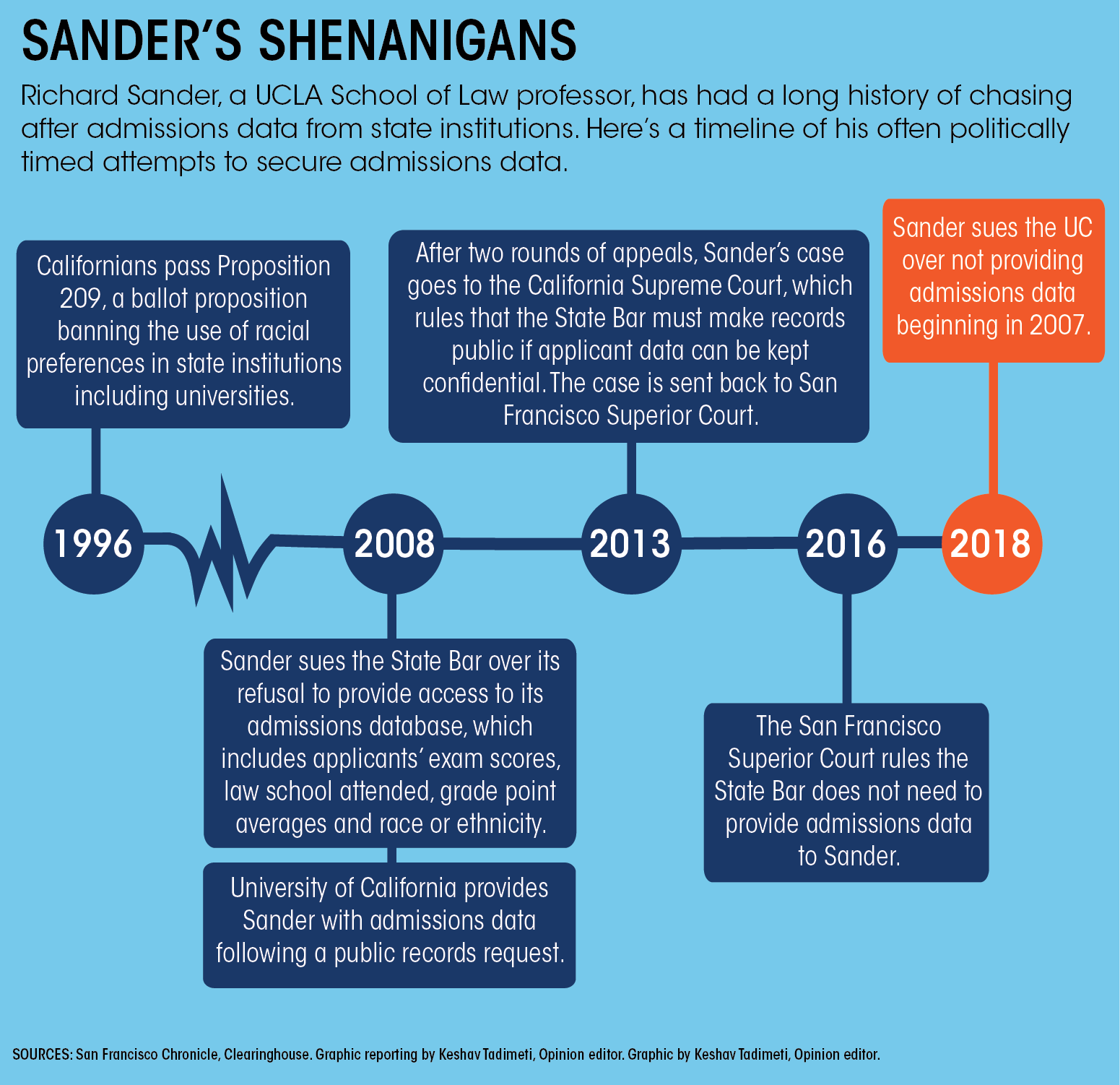

When UCLA School of Law professor Richard Sander filed his lawsuit against University of California two weeks ago, it was not to ban affirmative action. That – specifically, race-conscious admissions, the practice most often associated with affirmative action as a general directive – has been illegal in California public institutions for over two decades.

But in one of the most hostile environments for affirmative action since the passage of Proposition 209 – the 1996 ballot initiative that banned race consideration in admission processes – Sander’s legal action, nominally initiated for the sake of data transparency, may transform college admissions nationwide by triggering further scrutiny of university admittance practices.

Unlike other recent lawsuits against universities, such as the Harvard University trial that has attracted national attention, this one is not challenging UC admissions practices. Instead, it is an effort to crack open the massive black box of data that will allow Sander – and presumably others – to look at data that may allow for further legal challenges against universities. They suggest the UC is hiding something, as indicated by Sander and George Shen’s – a Chinese-American Republican activist – decision to concurrently release a recently obtained 2014 supplemental report by UCLA sociology professor Robert Mare that critics believe indicates Asian-Americans are disadvantaged in the UC admissions process.

Sander’s lawsuit complicates an already confusing debate on race and college admissions. While the lawsuit concerns the public’s right to view sensitive public institutional data, it arrives amid a reignited pair of debates that have long been forcibly merged together: whether or not race-conscious admissions runs afoul of constitutionally guaranteed equal protection rights and if Asian-Americans are “penalized” by the college admissions process in general.

The public deserves to see more data, but Sander’s motivations require contextualization in a larger, generally incendiary admissions conversation that has long been rife with misunderstanding.

The UC has denied it has broken the law in admissions, denying Sander a request made under the California Public Records Act and citing a recent decision by a state appeals court to throw out a very similar CPRA request he made for state bar admissions data. Sander claims he is being stonewalled by the UC – a feeling reporters everywhere know all too well. The UC has argued it is far too laborious to make applicants’ names and personal details anonymous in order to safely release admissions data to the public.

Even if the UC’s reluctance to release the admissions data – which would be of great interest to social scientists across the country – is suspect, it is entirely understandable. The UC doesn’t consider race, but race works its way into many aspects of life, and some of those things are considered in a holistic review of admissions. Considering factors like the applicant’s high school resources, area of residence, first-generation student status and “disadvantaged social or educational environment” help a portion of the applicant pool that is much more likely to include underrepresented minorities. Those who want to believe the UC is wrongfully considering race could easily ignore this and hastily conclude that race is the overriding or even sole determinant of admission.

It bears mentioning that Sander is not simply a free-speech advocate, but a determined researcher who wants information to support his faulty arguments on the impact of affirmative action. Sander is notorious for his mismatch theory, which argues that beneficiaries of race-conscious admissions fare worse academically at selective law schools than those who are not. Good data won’t fix mismatch theory’s untenable assumptions, such as the notion that black and Latino students – or any affirmative action beneficiary – do not and cannot improve academically. It also ignores the vast differences between law school and undergraduate admissions that make comparisons or extrapolations difficult and disingenuous.

A bevy of social scientists have repeatedly found mismatch theory to be an idea founded on analyses that are shoddy at best and deceptive at worst. In fact, research has instead found that underrepresented minorities do particularly well at selective schools. Despite this, mismatch theory remains a popular idea among affirmative action opponents.

Sander isn’t just wrong about mismatch theory. He has pointed to the purported success of the post-Prop 209 UC – not because of diversity, but because the millions spent on outreach programs have reduced mismatching – while calling it a natural experiment in race-neutral admissions. But precipitous minority enrollment declines that followed Prop 209’s passage have been mitigated by continued demographic changes in California that have greatly changed the applicant pool, and by admissions policy changes like the Eligibility in the Local Context program, introduced in 2001, that have benefited students in underserved communities.

Is the UC hiding something? Who knows. Do I wish the UC would reintroduce public statistical databases like StatFinder? Definitely. But filing a request for data under CPRA and subsequently suing for it is an unusual way for a researcher to ask for information. That’s because this isn’t a research data request, but a strategically timed, well-publicized effort to embarrass the UC and implicate it in what casual observers may construe to be a national, not just Harvard-based, effort to hurt applicants’ chances at admission, regardless of the credibility of the claimsmakers.

It is tempting to believe that having more public data will help us obtain “just the facts” about complex topics like admissions. Unfortunately, the facts are never just, and data exists to be interpreted and misinterpreted. Letting anyone tell the story of the data, as may happen if this suit succeeds, is dangerous and harmful for an already fraught affirmative action discourse in which misunderstandings prevail decisively.

And at a time when the public sorely lacks a precise understanding of admissions, we need more than good guesses from bad analysts.